Twelve Tips about Starting a New Open-Source Project

Here are some tips targeting developers who want to create an open-source project. They reflect my personal opinion and may not be all adapted to every situation.

Meet a need

So, you want to create a new open-source project? That's a good idea, but you need to understand very early why you want to do that. "Because it's fun"is not always a sufficient answer. Well, you can always learn by writing some software that will only be used by yourself and which will give you some experience, but at some point, you'll want your stuff to be used by other people.

- So, what is new about your project?

- Why do you need to create a new project instead of using or improving existing projects?

- What does it offer that is not brought by other projects?

- Why would people be interested in your project?

- Who are you targetting? Other developers with a new programming library, consumers, etc.?

- Are you confident that you'll be able to devote to that project an important part of your time for the next few months or years?

- Do you have sufficient experience and knowledge to be able to write your very own software?

Creating a software or a library is a tough but rewarding task. And it can be fun! You just need to think carefully about your project before you write a single line of code.

Be an expert in your language

So, you've chosen the programming language you'll be using for your project. Do you consider yourself as an expert in that language? Needless to say that you should already be experienced enough in the tools you'll be using. You'll need to know about all aspects of your language. If you're using object-oriented programming, make sure you know about all its subtleties.

For example, I've recently started a project using Python and OpenGL. Whereas at the time I started this project, I considered myself sufficiently aknowledged about Python, I clearly was not about OpenGL. So, I learnt OpenGL while I was developing my software. At some point, I realized I could use newer techniques that were much more powerful. More importantly, the techniques I was using then were in fact totally obsolete. My sources of documentation were simply completely outdated. I had to make important changes in my code in order to use the newer techniques. Had I be sufficiently aware about OpenGL before, I could have made the right decisions early on.

Write only in English

This advice only concerns non-English native speakers. I see many students in programming write code in some weird mixed language between their native language and English. There will always be some words in English in the code, be it only because of the English keywords in any programming language. I can understand the fact that someone is attached to their mother tongue, but the programming world is international. You can never be absolutely sure that some code you're writing today for yourself will never be used by someone else in the future. And that someone may not speak your language. How would you explain to that Chinese intern that he needs to learn Polish just to understand your comments in the code?

Of course, the same advice holds even stronger for any documentation you'd write. If you're not fluent enough in English, take lessons (and I should too).

Be an expert in your version control system

Using a version control system for any programming project is so natural and obvious that I don't even consider that as an advice... You don't even need to subscribe to an online service at first, you can just install a local distributed version system such as git or mercurial on your computer. Of course, at some point you'll want to host your code online, it's just so much more practical and secure. It's also nearly imperative when you work with different computers.

If you want your code to be both private and hosted online, you'll need to pay if you use Github. However, Sourceforge should let you do that for free.

Anyway, the point is that you need to understand most workings of your version control system of choice. If you're not familiar enough with it, take the time and learn it. It's important. It's the backbone of your code.

Now, I should really follow this advice myself and go learn git for good.

Programming is easy, designing is harder

Programming is easy. At least, it can be (especially with Python!). Children can learn the most basic aspects. Some languages are harder for sure. And the code can also be intrinsically involved sometimes, for example with concurrent and parallel programming.

My point is that programming is not necessarily the hard part. Designing is the tough one. Thinking about the perfect architecture for your code is, at least in my own experience, much, much harder than just "spewing out" code. Thinking about a coherent way of organizing your code into loosely-coupled modules, making your code simultaneously readable, flexible and efficient, designing a streamlined programming interface, these are the real challenges.

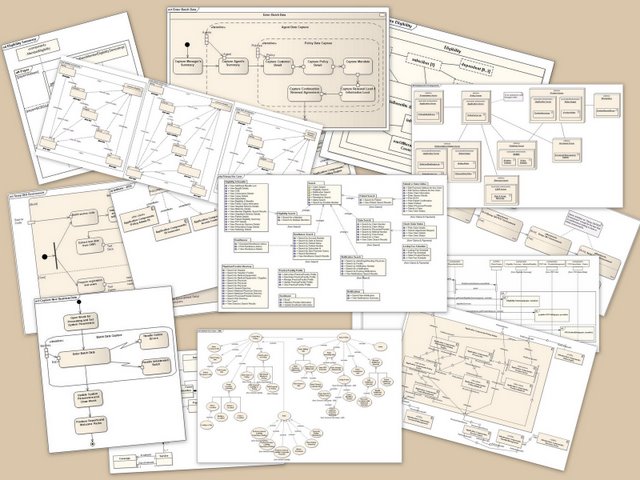

Unfortunately, I don't have any concrete advice about how to achieve that. I know that many people are using some formal methods for finding the prefect architecture, involving horrid swearwords such as "UML" and scary schematics with many boxes and arrows all over the place. I've never had the chance to learn that in school, and I've naturally been developing a more instinctive (who said bogus?) way of thinking about the big picture.

Take the time to think about the code you're writing. Is it smelling good? If not, think again and refactor. Is your code design rigid or flexible? Are you doing it the right way? Being constantly critical about your own code allows you to deal with badly designed code early on.

Don't spare the doc

Are you immortal and do you have an infallible memory? If not, you should document everything you do for your project. Document all your functions, with the details about the arguments and the returned variables (docstrings). Comment your code when it's unclear. Maintain separate documents about the global architecture of your code, about any decision you've made.

Trucks run fast. You may not be alive tomorrow. It would be a shame if your project disappeared with you, wouldn't it? Make sure you're not the only one to understand how your code works. Someone reading all your documentation should be able to maintain and extend your code without your help.

Don't spare the unit tests

I know that unit tests are important. Yet, I'm always lazy when it comes to writing them. I often prefer to test things manually. That's a terrible idea. Spending hours writing automated unit tests takes in the end far less time than testing everything yourself as soon as you make a change in your code.

A non-trivial software or library is a complex thing. It contains thousands of lines of code that are all related (well, they shouldn't be too interdependent if you have a good global code architecture). Fixing a bug somewhere can create a new bug somewhere else in the code more often than you'd thought (butterfly effect). That's the fundamental issue of non-regression. As you go along the development of your project, you want things to work better with time, not worse. When you fix a bug, you don't want it to reappear months later as you change some seamingly unrelated code.

The only way to be sure that this doesn't happen is to write automated unit tests. Writing unit tests is a real investment. It takes time initially, time that does not apparently make your software more functional. However, it does make it more reliable. And it can save you hours of debugging in the future.

Sometimes, the type of your software is not particularly well adapted to automated unit tests. It may rely on external web services, databases, or worse, it can contain a graphical part (or a graphical user interface).

For my visualization project, I thought for a long time that it was simply not possible to do automated tests. Yet, at some point, the code was becoming simply to large to allow me to test everything manually. So I had to take the time thinking about some way to write unit tests for the rendering engine. I found a solution, not a perfect one, but sufficient to let me know when things that worked before don't work anymore. For every rendering feature, I write a small script that uses it to draw the exact same white square at the center of the screen. Then, the rendered figure is temporarily saved into a PNG file, which is then automatically compared to a reference image. If the two images are different, the test fails.

It took me maybe one hour or two to make that work, but it proved extremely useful. For the week or two I've been using these tests, I've been able to find several bugs that were introduced by new, apparently unrelated features. I've then been able to fix them immediately.

You should write unit tests sooner rather than later.

Profile and optimize

Code readibility is more important than premature optimization. Yet, no one uses slow software or libraries. Make sure you profile and optimize your code regularly. When you code, think about design and readibility first, but do not overlook performance either, especially if you're in a time critical section (e.g. in a loop). When you code in a garbage-collected language like Python or .NET, make sure you don't create many temporary objects on the heap when you don't absolutely need them. Relatedly, use native structures instead of custom types as much as you can.

Don't overlook code quality

Make sure you're writing good code. Good not only in the design and architecture, but also just nice looking code. If your programming language has widely used guidelines, read them carefully and use them. For example, Python has PEP8. If there are tools for your language that automatically check the quality of your code, use them. Use spaces, indentation, and comments to structure your code and make it more readable. Code should not be something hidden behind a fancy GUI that comes with your software, it is part of your software and it's something you should be proud of. If you'd be ashamed to show your code to some other programmer, then you should seriously consider improving it.

Do some marketing

Do you want other people to use your software? If so, you should go find them, because they won't go find you. Target your audience. Check out mailing lists, groups, blogs where your audience hang around, and do some marketing. Prepare screenshots or videos if your software has any graphical part. Using Twitter is also a good idea. Be humble and open to the criticisms.

Get other people involved

If you want your software to be widely used and if it is an ambitious project, you'd better find other developers willing to work closely with you. An open-source project is all the more likely to be a long term project than there are people involved in it. Find good collaborators and help them understand all aspects of it. Alternatively, they can work on a specific and independent part (e.g. an external module or plug-in). If you're really serious about your project, you should have a long-term plan and consider its perpetuation after you move on to other projects.

Have fun

Finally, the whole point of open source development is to have fun (well, maybe not the whole point, but it's an important factor). You should be in love with your language and passionate about programming in general. Do you like sport more than programming? If so, just turn off your computer and do what you like.