A compiler infrastructure for data visualization

There are many data visualization tools out there. Yet, I believe we're still lacking a robust, scalable, and cross-platform visualization toolkit that can handle today's massive datasets.

Most existing tools target simple plots with a few hundreds or thousands of points: bar plots, scatter plots, histograms and the like. Typically, these figures represent aggregated statistical quantities. Maps are also particularly popular, and there are now really great open source tools.

Perhaps contrary to a common belief, this is not the end of the story. There are much more complex visualization needs in academia and industry, and I've always been unsatisfied by the tools at our disposal.

Complex visualizations

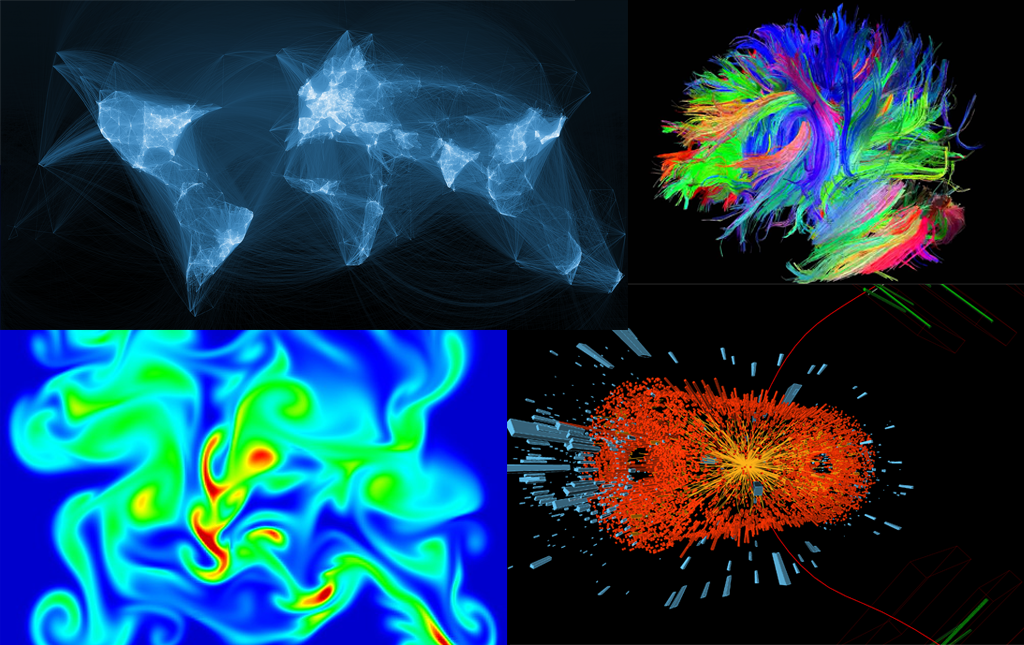

The complex visualizations I'll be talking about throughout this post are generally based on large datasets, and they may or may not be in 3D.

Large datasets

Most plotting libraries can't handle visualizations with millions of points. Crashes due to out-of-memory errors are not uncommon.

An often-heard counter-argument is that you're never going to plot millions of points when your screen rarely has more than a few million pixels. This is true with standard visualizations, but not with complex visalizations of raw, unstructured datasets, like the ones you may find in many scientific and industrial applications.

To give only one example in the discipline I know: neurophysiologists can now routinely record in animals' brains a thousand of simultaneous digital signals sampled at 20 kHz. This represents 20 million points per second. Recordings can last several hours or days. High-density 4k screens can now contain about 10 million pixels, maybe several times more in a few years.

The scientists I know absolutely do want to visualize as much data as possible. They may have two, three, even four HiDPI screens, and they're eager to see all signals in a given time interval, as much as their screens' resolution allows (and they're starting do to it with the visualization prototypes we're developing). This is an unprecedented opportunity to really see what's going on in the brain. There is no way around looking at the raw data directly, because they wouldn't know how to simplify the data or make statistical aggregates out of it.

I am convinced that the demand for these sorts of visualization is real not only in neuroscience, but also in genomics, astronomy, particle physics, meteorology, finance, and many other scientific and industrial disciplines that deal with complex and massive datasets.

3D

The second characteristic of complex visualizations is often 3D: most plotting libraries are designed for 2D, and when they support 3D, they don't do it well because 3D is implemented as an afterthought. On the other hand, 3D visualization libraries tend to be old, heavy, hard to use and to extend, and they do not support 2D visualizations well. There are more modern 3D libraries, like three.js for example, but they target video games more than scientific visualization.

Finally, there is always the option to resort to low-level tools like OpenGL, which no sane scientist will ever do.

VisPy: where we are now

These are all the reasons why we've started the VisPy project more than two years ago. We wanted to design a high-performance visualization library in Python that would handle massive datasets well, and where 2D and 3D visualization would both be first-class citizens. The main idea of VisPy is to transparently leverage the massively parallel graphics card through the OpenGL library for data visualization purposes.

VisPy now has half a dozen of core contributors and tens of occasional contributors. We've also just reached the highly-respected milestones of 666 stars on GitHub.

However, I personally consider the project to be still in its infancy. There is still a whole lot of work before VisPy gets to a mature and stable state. If the Jupyter developers admit considering the notebook (almost 5 years old, estimated 2 million users) as a "validated MVP" (Minimum Viable Product), I can definitely see VisPy as a proof-of-concept/prototype. This might sound crazy, but it's really not. To give an idea, matplotlib, the state-of-the-art visualization library in Python, is almost 15 years old; Python and OpenGL are about 25 years old; UNIX was developed half a century ago; and so on and so forth. We like to consider software as a fast-paced environment, but, in many respects, time scales can be much slower than what we think.

What will it take to bring the project to the next level? What can we do to ensure it lives through the next 5, 10, even 15 years?

Current challenges

For this to happen, I believe we need to rethink the entire logic of the project from the ground up. There are three main reasons.

A pure Python cross-platform library?

From the very beginning, we wanted a pure Python library. We were all using Python for our research, and we had all developed our own OpenGL-based Python prototypes for data visualization. Performance was excellent in our respective prototypes. We weren't using any compiled C extension or Cython, because we didn't need to. We were able to leverage OpenGL's performance quite efficiently thanks to ctypes and NumPy. So we decided to go with a pure Python library.

One of the many reasons was that we wanted to avoid compiled extensions at any cost. Packaging and distributing compiled Python libraries used to be an absolute pain. However, this is no longer the case thanks to Anaconda.

I'm now thinking that the whole "pure Python" idea is a bit overrated. None of the main scientific Python libraries (NumPy, SciPy, matplotlib, scikit-learn, pandas) is in pure Python. What does "pure Python" even mean, really? VisPy calls the OpenGL C API through ctypes: is it "pure Python"? Also, you could even argue that a "pure Python" program is being interpreted by CPython, which is all written in C... Finally, there are other great data analysis platforms out there that could potentially benefit from advanced visualization capabilities, like Julia, R, etc. That's not something you could do with a pure Python library.

Another problem comes from VisPy itself. VisPy implements a powerful but complex system for managing transformations between objects in a scene. Because it is in pure Python, there always have been significant performance issues. This is a critical problem in a high-performance visualization library that needs to process huge datasets in real time. These issues are now getting mitigated thanks to heroic efforts by Luke Campagnola. But it should come as no surprise that achieving high performance in a pure Python library is overly difficult. Spending so many efforts just for the sake of being "pure Python" is not worth it in my opinion.

Finally, the most important problem with being pure Python comes from a design goal that came slightly after the project started. We wanted to support the web platform as well as Python thanks to WebGL, the browser's implementation of OpenGL. The web platform is now extremely popular, even in the scientific community via the Jupyter notebook. Many data visualization libraries (like D3, Bokeh) are built partly or entirely on the web platform. More and more video games and game engines are being ported to WebGL. Given the efforts spent by the industry, I really believe that this trend will continue for many years.

How do you make Python work in the browser? The browser's language is JavaScript, a language fundamentally different from Python. I've been obsessed by this question for a few years. I've explored many options. Unfortunately, none of them is really satisfying. Now, my conclusion about Python in the browser is that it's never gonna happen, at least not in the way you might think (more on this later).

There is a similar issue with mobile devices. Sadly, apart from the excellent Kivy project, Python on mobile devices is getting very little attention, and I'm not sure that's ever going to change. Yet, there would be a huge interest in creating mobile applications from data visualizations made for the desktop.

I believe these are fundamental problems about Python itself, which, in the case of VisPy, cannot be satisfactorily solved with our current approach. We do have temporary solutions for now, VisPy does have an experimental WebGL backend that works in the Jupyter notebook (described in the WebGL Insights chapter that Almar Klein and I wrote this year), but it is fundamentally experimental. Because of the WebGL support, we need to stick with the lowest common denominator between the desktop and the browser. This means we cannot support recent OpenGL features like geometry shaders, tesselation shaders, or compute shaders. These issues are at odds with the idea of designing a solid codebase that can be maintained over many years.

Python and OpenGL

Another fundamental problem comes from OpenGL itself.

Modern OpenGL features a GPU-specific language named GLSL. GLSL is a C-like language that has nothing to do with Python. We believe that scientists should never have to write their own GPU code in a C variant. Therefore, in VisPy, we try to hide GLSL completely to the user.

To make this possible, we need to bridge the gap between Python and GLSL. The graphics driver typically converts GLSL strings on-the-fly for the GPU. In VisPy, we have no other choice than generating GLSL strings dynamically. We do this with string templates, regular expressions, parsers and so on. We have a large collection of reusable GLSL components (notably contributed by Nicolas Rougier) that are put together automatically as a function of what the user wants to visualize. Designing and implementing a modular API for this was extremely challenging, and as a consequence the code is quite complex. Again, this complexity is inherent to OpenGL and to our desire to generate visualizations on-the-fly with a nice high-level Python API.

There are many other problems with OpenGL. All sorts of bugs in the drivers, depending on the graphics card's manufacturer. These bugs are hard to fix, and they need to be worked around with various hacks in the code. Memory accesses in the shaders are limited. Interoperability with GPGPU frameworks like CUDA and OpenCL are possible in practice, but so hard and buggy that it's not even worth trying. OpenGL's API is extremely obscure, and we need to hide this in the code through a dedicated abstraction layer. OpenGL has accumulated a lot of technical debt over the last 25 or so years. Everyone in the OpenGL community is well aware of the issue.

This is one of the cases where you get the feeling that the technology is working against you, not with you. And there's absolutely nothing you can do about it: it's just how things work.

OpenGL's future?

All of this explains why I was so incredibly excited by the announcement made by the Khronos Group in March. They acknowledged that OpenGL was basically doomed (at least that's my interpretation), and they decided to start from scratch with a brand new low-level API for real-time graphics named Vulkan.

In my opinion this is just the best decision they could have ever made.

Compared to OpenGL, Vulkan is closer to the metal. It is designed at a different level of abstraction. Graphics drivers for Vulkan should be simpler, lighter and, hopefully, less buggy than before. Consequently, applications will have much more control on the graphics pipeline, but they'll also need to implement many more things, notably memory management on the GPU.

A major feature of the new API is SPIR-V, an LLVM-like intermediate language for the GPU. Instead of providing shaders using GLSL strings, graphics applications will have the possibility to provide low-level GPU bitcode directly. There should be tools to translate LLVM IR to SPIR-V.

OpenGL and GLSL will still work as before through via dedicated conversion layers, for obvious retrocompatibility reasons. There will be tools to compile GLSL code to SPIR-V. But applications won't have to go through GLSL if they don't want to.

This might just be the perfect solution for VisPy. Instead of mixing two different languages (Python and GLSL) with strings, templates, regexes, lexers and parsers, we could design a compiler architecture for data visualization around LLVM and SPIR-V.

Shaders and GPU kernels will no longer have to be written in GLSL; they could be written in any language that can be compiled down to LLVM (and, as a consequence, to SPIR-V). This includes low-level languages like GLSL and C/C++, but also Python thanks to Numba. Numba can compile an increasing variety of pure Python functions to LLVM. The primary use-case of Numba is high-performance computing, but it could also be used to write GPU kernels for visualization.

This could remove a huge layer of complexity in VisPy.

It might also be a solution to the cross-platform problems. We could potentially port visualizations to the browser by compiling them to JavaScript thanks to emscripten, or to mobile devices thanks to LLVM compilers for Android and iOS.

I'd now like to open the discussion on what a future Vulkan-based data visualization toolkit could look like, on what use-cases it could enable.

I should precise that everything that comes next is kind of speculative and depends on very partial information released by the Khronos group on early specification drafts. Also, I am well aware that this is a really ambitious and optimistic vision that might just be too hard to implement. But I believe it is worth trying. This journey is completely independent from the normal development of the VisPy library as it exists today. The two roads will only cross in the most optimistic case, and not before several years.

Before we see in more details how all of this could work, let's describe a hypothetical data visualization use-case that could come true with Vulkan.

Use-case example

There is a new data analysis pipeline that is going to process terabytes of data, and you're in charge of writing the analysis and visualization software. Your users have highly specific visualization needs. They want a fast, reactive, and user-friendly interface to interact with the data in various and complex ways.

You start to design a visualization prototype in the Jupyter notebook around your data. Through a Python API, you carefully design how to process and visualize the data on the GPU. This is not more complicated than creating a NumPy universal function (ufunc) in pure Python with Numba: it's really the same idea of stream processing, but in a context of data visualization. You describe how your data is stored on the GPU, and how it's converted to vertices and pixels. There is a learning curve, but it is not as bad as OpenGL/GLSL because you are still writing 100% Python code.

As part of this process, you also integrate interactivity by specifying how user actions (mouse, keyboard, touch gestures) influence the visualization.

At this point, you can embed your interactive visualization in a desktop Python application (for example with PyQt).

Now, your users are happy, they can visualize their data on the desktop, but they want more. They want a web interface to access, share, and visualize their data, all in the browser. The way it would happen today is that you'd hire one or two web developers to reimplement all your application in JavaScript and WebGL. Now, you have two implementations of the same applications, in two different languages, for two different platforms.

I believe we can do better.

You go back to your Python visualization. Now, instead of running it interactively, you compile it automatically to a platform-independent bitcode file. Under the hood, this uses the LLVM platform. You get a binary file that implements the entire logic of your interactive visualization. This includes the GPU kernels, the rendering flow, and (possibly) interactivity. In a way, this is similar to running a C++ program generating a function dynamically via the LLVM API, versus compiling a function to an LLVM bitcode file.

Once you have this file, you start writing your web application in HTML and JavaScript (maybe using some of the future Jupyter notebook components). But instead of reimplementing the whole visualization and interactivity logic, you compile your exported file to JavaScript via emscripten. Then, you have your whole interactive visualization in the browser practically for free.

Of course, this will only work if Vulkan is eventually ported to the browser. There are no such plans yet, Vulkan being such an early project at this point, but I suppose it will depend on the user demand. We might obtain more details during SIGGRAPH in a couple of weeks, where Vulkan could be discussed at length.

Now, your users are even happier, but they want even more. They want a mobile application for visualizing their data interactively. Again, you could compile your platform-independent visualization file to Android or iOS (both platforms are LLVM backends). Or maybe, who knows, mobile browsers will support Vulkan at some point, so your web application will just work!

Depending on your use-cases, the rest of the analysis pipeline can very well be implemented server-side in any language, like Python (potentially using Jupyter notebook components). It could even involve a cloud engine like Spark. The visualization logic could remain client-side, but you might have to implement custom level-of-detail techniques adapted to your data.

Architecture

What would it take to make this use-case a reality?

There are several components:

- A compiler API to specify interactive visualizations programmatically and compile them to platform-independent files

- A Vulkan runtime that executes visualizations on the GPU

- Optionally, a CPU runtime that executes visualizations on the CPU, as a fallback if a GPU is not available

The API will have to be designed at the most appropriate level of abstraction: higher than Vulkan, but low enough to support a wide variety of use cases. This would be the Vulkan equivalent of VisPy's gloo API, built on top of OpenGL. It would not have the limitations inherent to OpenGL.

The API would cover memory management with data arrays on the GPU, compilation of shaders and kernels, and the rendering workflow.

Language

In what cross-platform languages could we implement these components? At least for the runtime, Python is not really an option because it cannot run on the browser or mobile devices.

I believe that a sensible option (notably for the runtime) would be modern C++ (typically C++ 11).

I used to dislike old-style C++, however I discovered in C++ 11 a really different language. It is modern, safe, mature, with a wide community and solid documentation. The standard library looks reasonably powerful and well-designed.

C++ 11 can be compiled on many architectures, including JavaScript through the LLVM-based emscripten project. It seems to be well-supported on mobile devices as well. It is worth noting that the LLVM API itself is implemented in C++.

Obviously, choosing a relatively low-level language like C++ doesn't mean that end-users will have to write a single line of C++. There could be a Python (3-only, while we're at it!) library wrapping the C++ engine via ctypes, cffi, Cython, or something else. This is not really different from wrapping OpenGL via ctypes like we do in VisPy. Instead of leveraging a graphics driver that we cannot control at all, we use a C++ library on which we have full control.

While the runtime would likely be implemented in C++, the compiler could be written either in Python or in C++. If it is written in Python, other languages like R or Julia would need to implement it as well. But a Python implementation of the compiler might be an interesting first step.

The C++ Vulkan and CPU runtimes could be ported to the browser and to mobile platforms via the LLVM toolchain.

Library of functions

The compiler and runtime are just the core components. Then, to make the users' lives easier, we'd have to implement a rich library of functions, visuals, interactivity routines, and high-level APIs. Having a highly modular architecture is critical here.

There could be a rich user-contributed library of reusable pure LLVM functions, for example:

- geometric transformations: linear, polar, logarithmic, various Earth projections, etc.

- color space transformations and colormaps

- easing functions for animations

- special mathematical functions

- linear algebra routines

- geometric tests

- collision detection

- tesselation algorithms

- classical mechanics equations

- optics and lighting equations

- standard marker equations

- antialiasing routines

- font generators with signed distance functions

Most of these functions could be written in any language that compiles to LLVM. This includes C/C++, GLSL, but also Python via Numba, making user contributions much easier.

I should note that VisPy already implements many of these functions in Python or GLSL, so we could reuse a lot of code.

Memory model

Vulkan gives applications a lot of freedom regarding memory management. Therefore, we should come up with a simple yet powerful memory model that handles CPU-GPU transfers efficiently. One possibility could be to implement a NumPy-like ndarray structure that lives on both the CPU and GPU. It would be automatically and lazily synchronized between the two.

This is the option chosen by Glumpy, VisPy's sister project maintained by Nicolas Rougier. VisPy uses a more complex memory model where data can be stored on the GPU only; while this might save some RAM, it is more complicated to work with this model. Also, the host has typically much more RAM than the GPU.

SPIR-V has a nice support for arbitrarily complex data types, and a NumPy-like API could be used.

One significant advantage of Vulkan and SPIR-V over OpenGL is that the framework encompasses OpenCL-like GPGPU kernels as well as visualization shaders. Therefore, it would be possible to execute computation kernels on the same GPU data structures than those that are used for visualization, with no copy at all. Typical examples include real-time visualization of numerically-simulated systems like fluids, n-body simulations, biological networks, and so on.

Higher-level APIs

All of this represents the core of a relatively low-level data visualization toolkit. A core that would let users create powerful and scalable interactive visualizations in any language, on any platform, and with optimal performance.

On top of this, we could imagine plotting libraries with various programming interfaces. The hypothetical core I've been describing would be a sort of "game engine, but for data visualization".

Advantages

This vision represents a significant departure from the current state of the VisPy library. As a summary, I list here the advantages of choosing this path.

Future-proof

We can consider that OpenGL is on a rather slow deprecation road since Vulkan has been announced last March. Of course, OpenGL is so widely used that it's not going to disappear before many, many years. But by choosing to move forward with a brand new API, the Khronos Group sent a clear signal to the industry.

I also believe that LLVM has a clear future.

Truly cross-platform

By moving forward with a C++ core and an LLVM-based compiler architecture, we obtain a truly cross-platform framework. We are not prisonners of a given language like Python, but we have the possibility to target various low-level and high-level languages at leisure. We have potentially access to x86-64, ARM, desktop, mobile, and browser platforms.

This is made possible thanks to great projects such as LLVM, emscripten, clang, and Numba.

Modular and extendable architecture

A modular and extendable architecture is key to a future-proof and sustainable software project. An architecture designed around a compiler, a runtime, a library of pure LLVM functions, and a small number of APIs should meet these criteria.

A "pure Python" end-user experience

Perhaps ironically, achieving a "pure Python" end-user experience is made possible by designing a compiler architecture around C++ and LLVM, not by writing a 100% Python engine... I think that having an entire codebase in Python is not a requisite for being pure Python; however, having an entirely Pythonic Python API is. That your Python code leverages CPython, a C++ library, or is being compiled straight to LLVM IR or assembly doesn't matter much from the user's point of view. It's still "just Python".

Access to modern GPU features

Vulkan gives access to modern GPU features such as geometry shaders, tesselation shaders, and GPGPU compute kernels. This allows for an exceptional degree of customization in complex visualizations.

Optimal performance with C++

Being a pure Python library, VisPy needs to resort to many tricks to achieve good performance. For example, every OpenGL call is quite expensive, because of the driver overhead, but also because of the Python bindings. For this reason, we need to batch as many calls as possible on the GPU. This is the main motivation for the collections API, where severaly independent but similar items are concatenated together and rendered at once on the GPU. This is a somewhat complex system.

With a C++ engine and Vulkan command buffers, implementing collections might be unnecessary. We could still batch-rendering calls, but on the CPU instead of on the GPU, which is much easier. Performance might be similar than VisPy's collections, but this remains to be tested.

More generally, on the CPU side, we have much more freedom on the algorithms we can implement. For example, implementing polygon triangulation should not represent a major problem, whereas it would be much more complicated in Python. Since it's C++, we're no longer limited by CPython's performance.

GPGPU-powered visualizations

The ability to combine compute kernels with visualization kernels on the GPU is also a major advantage of the system. This feature basically comes "for free" with Vulkan, and it is no longer necessary to mess with arcane interoperability commands.

Conclusion

Since this is such a major departure from the current state of the project, the system discussed here should be explored independently from the development of the VisPy library. This is an experiment to investigate a radically different system based on a brand new low-level graphics API.

Obviously, these are just ideas that need a lot of discussions, and many details need to be worked out. But I think this is a really interesting project to pursue.

If this experiment is successful, the system could potentially become the basis of VisPy in several years.