Writing the IPython Cookbook

My latest book was released a few weeks ago. This project has been one of the most challenging projects I've ever done, and not necessarily for the reasons I would have originally thought. Here is a little story of those fifteen months writing the IPython cookbook.

The story begins shortly after the release of the IPython minibook, my first book, and the prequel of the cookbook. The editors proposed me to write a follow-up to this introduction to IPython, and I accepted. I had felt limited in terms of page count while writing the minibook, and I thought it would be a great idea to expand further on the subjects I couldn't develop properly in the minibook.

The only constraint was that this new book would be a cookbook. This was a very strong constraint. The book had to be a collection of short focused recipes, each tackling a very specific problem.

I then spent a few days working on a detailled table of contents. My idea was really to expand on the topics addressed in the minibook, namely the use of IPython and the scientific Python stack to solve problems in numerical analysis and data science. I came up with a list of fifteen chapters covering a wide range of the subject.

I organized the timeline of the next 6-9 months with the help of the IPython developers. IPython 1.0 had yet to be released, but I wanted to target 2.0 in order to cover the interactive widgets. I had to organize my work carefully, because I was going to start the writing before the availability of some critical features. For this reason, I was unable to write the chapters in order. I came up with a very precise writing order, with the chapters depending the most on the widgets being due last. For example, I planned to write the chapter dedicated to the notebook last, whereas it is one of the first chapters in the book.

Having such a rigid cookbook structure for the book made it easier to plan the writing. Since all recipes were relatively independent, I could create them in any order and even in parallel.

In the end, it was clear to me that this would be a hard and challenging project. I just had no idea that it would be that hard.

Planning

I started to lay out the list of recipes in every chapter. I wanted to cover a broad range of the subject without entering too much into the details of every method. Further, I also wanted to illustrate all methods on various real-world examples.

I kept a few text files with all ideas I had and a provisional list of recipes. Using simple text files using the Markdown syntax, synchronized with Dropbox, is the most effective way I know to keep notes organized. I had tried Evernote and other similar services, and I always ended up coming back to my little text files. It's just so simple and effective.

Over the course of many months, I would constantly update my notes as ideas went on. I also kept a bookmark folder with all interesting websites I could find. This would become the main source of references for the book.

I then started to write the very first chapters over the summer.

I had a precise and relatively tight timeline imposed by the editors. I chose to stick to a virtual timeline, much tighter, by security. This way, I would always be ahead of schedule, or at least I wouldn't miss the editors' timeline.

In practice, this proved to be essential. Since my virtual timeline was so tight (a couple of weeks per chapter), I always had to push back a bit the remaining deadlines. But I always managed to respect the official deadlines. I also made use of the few months before the official start of the writing; I was able to start the writing early and always be ahead of schedule.

Microsoft Word and the notebook

Like for the minibook, I started to write the book in this wonderful program called Microsoft Word. As all programmers know, writing text and code examples in Word is a real joy when we're used to text editors (and yet, I'm not a vi or emacs guru, I only use graphical text editors). Since the publisher's workflow is built around this program, I had no choice but using it for the book. I set up a few keyboard shortcuts to make the experience less painful, but it became clear that it would be nearly impossible to write 500 pages of text, code, and mathematical equations in Word. The only tool I wanted to use was obviously the IPython notebook.

At first, I had a small Python script that would convert notebooks to formatted ASCII text that I could copy and paste in Word. I could write and test the code in the notebook. I did that for a couple of chapters, and then I gave up. I just wanted to write everything in the notebook, not just the code. Text (rich text with bold, italics, etc.), lists, input code, output text, figures, equations, references, links, Tip boxes, and so on and so forth.

So I tried something crazy. I investigated the possibility to write a full notebook-to-Word converter that was adapted to the Word template provided by the publisher. I knew that automating this process would take a lot of work, but would be beneficial in the long run. After all, I had more than one hundred recipes to write (one recipe = one notebook).

I explored a few options, notably using the Open XML format, or using COM (an inter-process communication framework for Windows). I can't remember exactly why, but I decided not to use Open XML. I might have thought that I had to use the old .doc format, because the publisher was still using old versions of Word (I'm not sure if that's true anymore). Anyway, I ended up playing with COM in Python.

It wasn't as bad as it sounds. Word's COM interface is okay, and using it from Python is straightforward (I was "fortunate" enough to be a Windows user at the time). I wrote a small Python class to write documents programmatically from Python, and using the .dot template that had been provided by the publisher.

The hard part was actually to write the converter: parsing the notebook's JSON, including Markdown text. I basically had to write my own Markdown parser using a battery of regular expressions in order to support lists, equations, code, and so on. It wasn't an easy task, especially given that I was running out of time. I could have used an existing Markdown parser but I didn't manage to use them properly. My quick-and-dirty converter seemed to work okay, although not very quickly (the bottleneck seemed to be due to the inter-process communication anyway).

For images, I wanted to have the possibility to integrate images with the Markdown syntax, or to use matplotlib figures. For the latter situation, all I had to do was to save the plots in PNG and integrate them in Word. I used a custom matplotlib parameter file, notably to use a higher DPI.

Supporting LaTeX equations was harder. I didn't manage to convert them into Microsoft Equations, and I wasn't sure they would be supported by the publisher anyway. So I decided to convert all equations to images. I took some code from matplotlib to do that, using my local LaTeX installation.

I used cell metadata in the notebook to specify some formatting options, like Tip boxes.

Eventually, after maybe a month of work, I ended up with a command-line tool that took a list of notebooks and generated an entire chapter in Word, perfectly and entirely formatted. This was a clear victory, because it meant that I was able to write exclusively in the notebook without even thinking about Word. It meant I could just focus on the text, the examples, and the code, and not on how unhappy I was to use Word.

If only I knew what would come next.

In the meantime anyway, I was relieved.

The first draft

I wrote the first draft within several months. The hardest bit was to find interesting examples and use-cases illustrating each method. I tried to use examples from a wide variety of disciplines in order to emphasize the wide applicability of the Python scientific stack today.

Finding compelling open datasets that could be used to illustrate specific methods wasn't easy. Getting a good idea is not enough: you have to test it and check that it gives interesting results.

The rigid structure imposed by the cookbook format was both interesting and challenging. Every recipe had to contain an introduction, a list of installation instructions and requirements (Getting ready), a numbered list of steps (How to do it), the explanations (How it works), a discussion (There's more), and a list of references. At least I didn't have to care about the structure as it was all imposed to me. However, some recipes didn't fit this outline very well. The constraint of putting the instructions before the explanations didn't always work. Sometimes you want to understand what you're doing while you're doing it, not after. Some recipes were also a list of tips rather than a list of instructions. So I had to fight a bit with the editors to alleviate this constraint in a few recipes.

Eventually, I had finished all recipes by the end of the winter.

The revisions

Shorty after, I started to receive the first reviews of my chapters by the technical reviewers. This is where my notebook-to-Word workflow started to be problematic. The reviews were made in the Word documents themselves (sent by e-mail), using this awesome Track changes feature. So I had to make corrections in the Word documents themselves, not in the notebooks. Since I didn't have the time to make a reverse Word-to-notebook converter, my process was unidirectional. There was no going back. Once I'd started to edit the automatically-generated Word documents, I couldn't go back to the notebook, and the two versions diverged permanently.

All code changes had to be done twice: in the text, and also in the notebook (so that future readers get the last version of the code by downloading the notebooks).

The reviews were globally positive, and I didn't have an enormous amount of work to do for the revisions.

That being said, I had to add a few new recipes, because some subjects were not sufficiently covered in the first draft according to some reviewers. This was something unusual at this stage, so I had to convince my editors to let me do it.

Finally, I finished the second draft within a couple of months.

The editing process

Once all the writing was finished, the next stage started. The goal was to go from the revised manuscript in Word to a corrected, proof-read, edited, laid out PDF. Perhaps surprisingly, this proved to be by far the hardest and most painful experience ever.

A team of half a dozen editors appointed by the publisher started to process the entire manuscript in parallel to check for errors, inconsistencies, typos, grammar errors, and so on. That's the theory. In practice, this stage ended up in a chaotic nightmare.

First, all editors had different ways of working, different opinions on the many conventions that compose a book, and were differently zealous. In the end, every chapter looked different in the way the recipes were organized, the links and references were presented, and so on and so forth.

Second, some editors decided unilaterally to change the formatting of some words, to add or delete some words here and there, or even to delete entire paragraphs. These changes would make sense when they are motivated by actual issues in the text. However, this wasn't the case in the majority of instances. The worse part is that these changes would make a sentence or a paragraph incomprehensible, misleading, or just plain wrong. I often had to look back in the original version to understand what I originally meant and to fix the change.

There could be hundreds of such changes in a single chapter (multiplied by fifteen chapters). Word's Track changes feature made the process even more enjoyable. It not only tracks changes in the text, but also formatting and many other non-relevant changes. In the end, the actual changes that could result in errors were flooded within thousands of non-relevant edits. I couldn't find a way to automatically filter these non-relevant edits.

Oh, and if you forget to enable Track changes, then your changes are completely lost. This is because Word tracks actual changes rather than comparing two versions like a sane version system like Git would do.

I spent tens if not hundreds of hours tracking and correcting these edits. It is ironic to think that this process was supposed to increase the overall quality of the book. If I hadn't been sufficiently vigilant, many "new" errors (introduced during the editing phase) would have slipped by.

At the same time, the editors were instructed to try the code and check that it didn't contain any virus (sic). These poor souls had no programming experience and had to try all the code of this advanced-level book. I could see they were completely lost when they asked me why random() didn't return the same number as in the book when they tried it. I had to fight and convince the publisher that this was nothing less than a pure waste of time for me and the editors to try out all the code this way. I ended up doing this step myself.

I was lucky enough to be aided by a few trustworthy people during this process, because I probably wouldn't have managed to do it on my own.

Later in the process, it was decided that all equations would be reformatted by the editors with an adequate equation tool rather than with images. I also had to track down these hundreds of instances. There were a few errors, but it wasn't as bad as I feared.

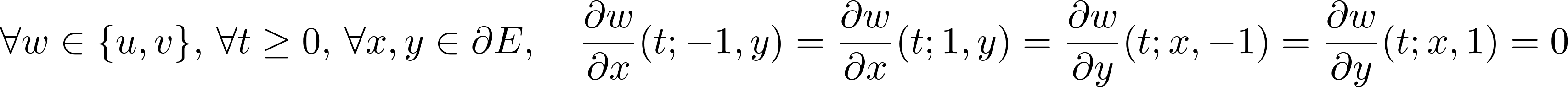

Still, look at the life cycle of this little equation. As any self-respecting equation, it started its life as LaTeX code.

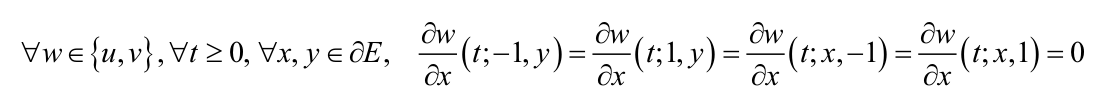

The conversion to Word resulted to a few minor mutilations.

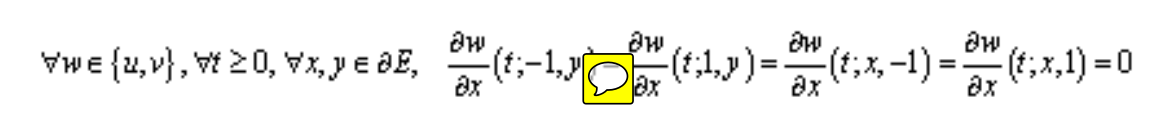

For an unkown reason, it suffered a lot during its conversion to PDF.

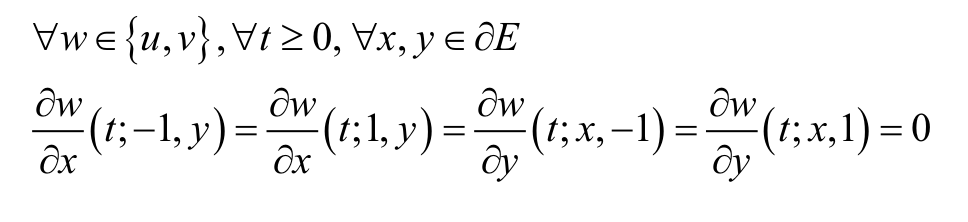

Fortunately I spotted out the problem and had it corrected.

Conclusion

In the end, I managed to finish the editing phase in time, and the book was finally published late September. It was by far the hardest and most tedious experience I've ever done.

The main conclusion of this is that I'm now convinced that Word is an abomination. I think it is one of the worse human creation after the atomic bomb. Everyone knows that writing in Word and sending over chapter3.rev57.new.new-old.rev-final.doc files by e-mail is a nightmare, but no one really knows until they have to do it for real with a 500-pages book full of code listings, images, mathematical equations, and URLs.

Text files. Markdown. Distributed version control systems. Diff and merge. These are the right way to work collaboratively in the 21st century. Anyone thinking otherwise is stuck in the last millenium.

I won't start any new project if I'm forced to use Word, and you should do the same.

Recently, I read this. I also stumbled over this and this. Integrating the IPython notebook in these toolchains should be doable. I can't imagine working with anything else from now on.